Let's return to the self and the Self. The big-S Self seems to be much more compatible with some form of nativism than the small-s self. I won't discuss the possibility of a spiritualistic or metaphysical nativism for the Self as I am really only interested in psychological theories, not religious ones. So, what is innate in the Self would be seen as genetic. There are two major components of the innate Self: species characteristics and individual variations/predispositions. In the personal experience of the Self phenomenon, the individual is commonly confronted with what feels like predisposition that cannot be eliminated or entirely avoided. Colloquially, it might be called the "true self". That term can be misleading, but the experience of this self/Self is often felt as a kind of fate or destiny that must be satisfied and largely obeyed.

I prefer not to attach anything metaphysical to this feeling, but I don't think it should be dismissed. There are many elements of psychological character and aptitude or predisposition that seem to be unique to each of us and with which we have to contend in much the same way we have to contend with being a certain height, having a certain body structure, a certain hair or eye color, and so on. That traits such as these can be passed on genetically is entirely accepted and scientifically valid. If we are to claim that psychological and emotional predispositions have no genetic component, we have a great deal of arguing to do and heaps of evidence to provide to contradict reason.

That we inherit psychological predispositions (in some form) seems hardly worth questioning to me. But predispositions are not predeterminations, and the degree of plasticity and interpretation possible for such predispositions does seem to be significant. It depends on how we look at these predispositions. Sometimes, they feel like absolute decrees or impossible barriers to modification. Other times, interpretive expression can feel almost limitless. What no doubt fascinates many classical Jungians is the affect we feel in relationship to these perceived predispositions. At times, these perceptions carry what feels like divine will or meaningfulness or numinosity. We wrestle with angels in the quest to either be or not be ourselves.

The developmentalist perspective would probably not disagree or ignore this phenomenological observation. But instead of interpreting these feelings and indications of "primal" influence as biological or genetic, the developmentalists would see them as having developed in the first few years of life (and also in utero). The mystique of self/Self and the numinous power of the archetypes is attributed to these early, formative relationships between the infant and the mother. At the most basic level, it may appear to be a toss up: heads, archetypes emerge out of the infant/mother relationship; tails, archetypes emerge out of instinctual, biological predispositions. If this were the case, it would be understandable to see Jungians split 50/50 on the issue, half nativist, half developmentalist.

But the evidence is not so evenly divided under closer inspection. When we examine archetypal phenomena, do we find numerous indications that they are shaped wholly by infant/mother relational dynamics? Or do we see that archetypal phenomena accumulate around human behaviors common to various stages of life? Unequivocally, the latter is true. In fact, most of the archetypes one encounters in an individuation event do not seem to be directly dependent upon infant/mother relational dynamics. This is not to say that the infant/mother dynamics are not archetypal, merely that it is extremely unlikely that they can account for all of the archetypal phenomena. Interpreting archetypal phenomenon with an insistence that they derive from infant/mother dynamics is massively reductive and in my opinion only necessitated by ideological rigidity.

I prefer to look at psychological development as the gradual self-organization of a complex adaptive system. I am not saying that mother/infant relations are not profoundly important to development. But instead of reducing all life stages to the infantile, I think it is more accurate and functional to consider life stages as environments (recall above, the idea the EEA as a cultural or informational/relational environment). One of the difficulties in constructing an EEA, even as a cultural environment, is that even in the modern world, we live in different cultural environments throughout our lives. It may be helpful to think of these environments in terms of our adaptedness to them. So, for instance, an infant may become extremely well adapted to the environment of the mother/infant relationship . . . but that adaptation is not directly applicable to survival in the pre-adolescent peer environment (or perhaps even in the environment of the father/child relationship). Adaptedness to the pre-adolescent peer environment may not serve one well in the attempt to adapt to an adult environment. Adaptation to strong peer environments may not serve one well when adapting to individual relationships.

I can agree very abstractly with Freud and many psychoanalysts that it often seems as though we carry over methods of adaptedness from an earlier stage to a later in ways that prove unadaptive to those later environments. I wouldn't locate these stages all in infancy, though, or connect them to specific body parts or functions. I would grant, though, that successful adaptation to an earlier environment is mostly beneficial to learning how to adapt to a later environment. Therefore, where and individual appears to have difficulty adapting to, say, an adult environment, we are likely to see an over-reliance on adaptive strategies employed in an earlier environment (infancy, childhood, adolescence, etc.). Even in the earlier environment, these strategies may have been flawed. It seems very likely that the development of functional early strategies is largely dependent on the quality of the environment (typically, the parents). Where the environment is not (to borrow Winnicott's term) "good enough", adaptation strategies are likely to develop less functionally . . . where less functionally often means with diminished flexibility.

In such circumstances, emphasis on development of a small-s self (where this self is a strategic environmental adaptation mechanism of sorts) is entirely warranted. That self is constructed in relation to its environments. That is, it exists and can be identified as occupying a psychic "shape" that would fit more or less seamlessly into the environments it must adapt to in order to survive. One of these environments or environmental factors would be the big-S Self. It presents some shaping influence on the small-s self/ego. Often enough, there is a noticeable conflict between the Self and the actual environment in which the individual lives. But the small-s self does not typically have the adaptive strategies required to negotiate this conflict very gracefully during early childhood. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the mother or the parents/caretakers become the receptacle for projections or transference of a Self figure (I prefer figure to "object", which is the more conventional word used in object-relations theory). In infancy, where the environment is typically dominated by the figure of the mother, the mother is essentially responsible for welcoming the Self into the environment (where it can, if only subconsciously, be recognized and validated by the infant). We seem to be predisposed to seeing the Self only outside our sense of self, to seeing the Self as Other. Something environmental always needs to catch the Self's reflection in order for us to recognize it.

For the infant, this is the mother who engages in mirroring the child in a way not dissimilar to the way the psychotherapist mirrors the patient. That is, the mother and psychotherapist both lend validity to the expression or externalization of the child's/patient's emotional and psychological being. Mirroring is a word common in developmentalist language, and although I don't reject it, I prefer to use the term "valuation". Mirroring can get entangled in ideas of narcissism, and I find this distracting from what I mean by valuation. Of course, in psychoanalytic theory, narcissism is a robust concept with some forms or degrees of narcissism being "healthy". But I think it is less accurate to prescribe a certain kind and amount of "self-love" than it is to prescribe self-recognition and self-acceptance. So often we need to be able to see ourselves doing or being or feeling or relating or suffering in order to adequately understand the validity of these things. Our behaviors and reactions are not inherently fantasies or illusions or figments of the imagination that we should just be able to think away by brute force of will. The valuator facilitates the appearance of the valuated. And the relationship is reciprocal.

The mother may valuate and facilitate the child, but the child also valuates and facilitates the mother facilitating the child. In analysis, the analyst may facilitate the emergence and recognition of the valued Self for the patient, but the patient's recognition and acceptance of this, in turn, facilitates the analyst. These kinds of interactions are cloaked in clinical terms by analysts, but I believe the phenomenon is broader than what the analyst's office allows. In all of our respectful and empathic interactions with others, we can facilitate, valuate, and essentially mirror the other. We construct one another in this way (although also in negative or destructive ways when we fail or refuse to valuate the other we interact with). We could call it the care and feeding of the soul.

Despite my many agreements with the developmentalists about the importance of the mother/infant relationship, I part ways with the developmentalist paradigm where it seems to emphasize predetermination of adult psychology by infant relational experiences. To me, it seems that the developmentalist paradigm stacks the building blocks of personality one on top of another. So any imperfection or instability in the foundational block (mother/infant relationship) leads inevitably to the instability of the whole tower . . . and perhaps to its collapse. I do not deny that, in cases of early trauma, a "crack" in the foundation could eventually give away under the weight of what is built on top of it. But this linear, vertical notion of personality is, I believe, a flawed analogy. A complex system commonly develops around imperfections. It's robustness can counteract many elemental deficiencies. Even when the elemental deficiencies remain. Sometimes what is broken and heals becomes stronger than what was never broken. It is this basic concept (based in observation) that stimulates the enterprise of initiation. Ideally the initiation mirrors the survivable self/Self that is latent in the child by recognizing it, holding it up against some form of ritual assault or death. We may never know the shape and function of our resilience unless it is tested.

But childhood traumas are often prolonged over many years (perhaps over the entire childhood). In these situations, what is being built on top of or around the foundation of the mother/infant relationship is just as shoddy. The elemental flaw is not compensated for or reconstructed into something more complex and robust. Instead, it shines through, acting as a kind of emblem of the dysfunctional ego. Ego strategies are constructed with a distinct possibility of choice, but children are rarely very good choice-makers, especially in traumatizing situations. Moreover, the choices we have in the process of ego construction are rarely apparent to us both as children and as adults.

Where the developmental and psychoanalytic clinical methods revolve around regression of the patient, I would suggest a slightly different metaphor is more apt. The goal should not be to regress a patient back to an infantile state (where they can supposedly start over with the analyst's guidance and containment). This metaphor relies on a notion of personality that can be disassembled into elemental parts, a kind of Mr. Potato Head psyche . . . where the analyst seeks to take the patient back to the original, unadorned potato. On one hand, I suspect that state of regressed infanthood is a fantasy constructed as part of the psychoanalytic theater. We are not really Mr. or Ms. Potato Heads with removable psychic parts. We cannot be broken down to genuine infanthood. We can only fantasize and role play our adult concept of what the infant is and feels. The value of this theater is highly questionable. I don't deny that it could be, at times, functional. But I also note that it has many potentially dangerous side-effects, e.g., prolonging analysis by creating a dependency on the analyst.

But I think there is value in a process that parallels regression. I often call it dissolution. Dissolution is what initiation rituals mean to utilize and what was being represented in alchemy by the Mercurial bath or acid that dissolves Sulfur or gold. As with regression, layers of ego construction are being stripped away. But in dissolution, this doesn't lead to infanthood, to helplessness and pre-verbal, volcanic affect suited to an environment defined by the (good-enough) mother/infant dyad. Dissolution is meant to unlock some kind of deep resiliency or survivability. In initiation, this resiliency is what enables the initiate to survive or pass through the initiation. This deep resiliency is experienced as "not me". It is Other, and yet it also seems to be within. Essentially, it is instinct or basic life drive/libido.

In alchemy, dissolution is meant to enable the pageant of color: first black, then white, then red. In black (Nigredo), there is death, and yet it is a fecund death, a death that is holding the seed of life, "spontaneous generation", death and rebirth. More psychologically, we could say that dissolution allows us to see the seams in our ego constructions, their arbitrariness, the fact that these constructions were made by specific choices unconsciously made as if inevitable, yet now there seem to be alternatives. And with an adult mind (not a regressed infantile mind), we are equipped to make new choices of construction . . . or at least to add reparative complexity and robustness to these initial, rigid and fragile choices. Of course, this choice-making is more complex than I have made it seem. Not only does one have to contend with the habitual and sometimes Demonic pull to make the same old (poor) choices again, one must also contend with the Self. The Self seems to exhibit a will of its own, and although we might realize that our new choices need to honor this will, many of the choices the Self seems to call for are not immediately practical or even possible. The ego then stands between the Self and the Demon (or superego or worldly conforming pressure), creatively negotiating. Even when we recognize what we must choose, it is difficult to figure out how to make this choice survivable.

Despite what seems like creeping into the mythopoetic here, I see it as quite possible (even likely) that this resilient seed which dissolution is directed at exposing and recognizing is fundamentally biological. On one hand, as an organized drive toward survivability and adaptedness, it makes sense that there would be a biological component. We still have no scientifically neat term for this life force, only the fairly deprecated "libido". I'm not sure we have to wholly dispose of a libido theory, but we must take every precaution not to over-simplify this libido as Freud did. Libido as a term may no longer be extractable from its romantic, psychoanalytic connotations, but as a placeholder term, it does still describe what appears to be a complex dynamic system of organization. It is less "basic drive" than it is an organizer or something that has emerged from a complex self-organizing principle. Along with Jung, I agree that whatever this libido is, it is not purely sexual, nor is it infantile. It operates not where the infantile resides, but where there is a need to adapt to an environment and to survive.

On the other hand, this essential biological phenomenon as we encounter it is not merely a m organizing life force principle. It is also commonly laced with structure. It doesn't merely say, "Survive!" It also contributes some conditions that shape the specific form of survival needed. That is, this Self pushes not only for generic survival but for survival specifically in a given form or set of limitations . . . survival as who we "really" are. There is no universal expression of the Self. It is like writing poetry in traditional form. The form constrains the shape and sound (and arguably, to some degree, the content) of the poem. Yet, the variations within the constraints of the form are still nearly infinite. We can call many poems sonnets or villanelles, but no two of any form are entirely alike (or ever seek to be!). As with the expression of DNA, there is constrained diversity.

What the initiate finds in the deep state of dissolution is not merely absence or emptiness or void. Rather, the inherent structure of the syzygy is revealed. That is, the component figures or processes of the animi work: the hero and the animi. The animi represents the developing relationship with the Self, and the hero is the personality structure capable of facilitating and valuating the Self (as animi). It is not an inevitability that dissolution will lead to fully realized animi and hero constructs. More often than not, dissolution proves unnavigable for most people . . . especially today when there is no institution of initiation or experienced guidance through the dissolution process. Without these cultural institutions, the animi work cannot be prescribed, and so cannot be made an essential part of a psychotherapeutic process. Initiation is a dangerous venture. It always has been. As a result, those who venture into the animi work today are mostly those who are "Called" or compelled. It is not an effort at enlightenment, but a necessity of survival. Where it is not a necessity of survival, the animi work will not likely succeed.

When we talk about psychological phenomena like the hero and the animi archetypes, we are talking about something that did not develop in early infant/mother interactions. These psychic structures do not fully emerge until at least adolescence, much in the same way puberty emerges. Environmental factors do influence the emergence of the syzygy, much as they can puberty . . . but the "plan" for puberty is genetic or innate. With the physical and psychological changes puberty thrusts upon us, we often find ourselves asking for the first time who we really are objectively. And what we usually find, if only subconsciously, is that we are many selves, many potentials. The choices we have, our unfixed, Protean identity, seem nearly endless. What hand shapes us . . . has shaped us, and will shape us in the future? We are not really ready to decide. We have almost no knowledge and experience to go on. We exist as practically a traded good awaiting purchase.

The convention of modern civilization (especially in Jung's and Freud's era) is that the superego purchases identity around adolescence. And the "well-adjusted" individual rides that wave of construction. Instead of dissolved and initiated, the pre-adolescent ego is employed or impressed into the service of cultural maintenance. While this may require discipline and hard work (i.e., obedience and not asking too many questions), it is not based on the principle of egoic transformation that initiation had long been the archetypal expression of. Perhaps more importantly, tribal initiation prepared the individual to be a responsible member of the tribe, a facilitator of the tribe and its identity constructions (of the tribe-as-Self). Modern indoctrination into adult life, because it does not operate on an initiation principle, tends to "breed" detached/unrelated citizens with little or no concept of group facilitation. Alternatively, individuals are indoctrinated into tribalist groups or modern subcultures where the powerful pull of participation mystique encourages a specific identity construction, but no "elder" maintenance of the tribe operates to help keep the tribe adaptive in the modern environment. Therefore, the identity constructions it disseminates to its members are themselves both uninitiated and maladapted.

For now, I will not go into the intricacies of unconscious/compulsive tribalism in the modern world and will return instead to the initial focus on developmentalism and the idea that individuation occurs in childhood as well as adulthood. To repeat the quote from Jean Knox:

Michael Fordham, one of the founder members of the Society of Analytical Psychology, was not happy with Jung's view that individuation was a task undertaken in adult life only and not in childhood. His work with children at the London Child Guidance Clinic, before the Second World War, had shown him that children's dreams and paintings were rich in archetypal imagery and he was increasingly convinced that these dreams and paintings were not simply reflections of the parental unconscious expressed through the child (Fordham, 1993).

Here, Fordham seems to be envisioning individuation as the process of becoming whatever individual we become (the small-s self). By contrast, in Jung and the classical Jungians, individuation is a process of becoming the individual we were "meant to be" (as defined by the big-S Self). Where I use the term individuation, I mean the process of differentiating oneself from others, from our groups, and from our affiliations and affiliated identity-constructions. It is part of this archetypal movement of differentiating ourselves from the other to also differentiate the other. That is, to recognize her/him as other and eventually to valuate that otherness. In other words, relationship is not rated by how much one identifies with the other, but by how much one accepts and valuates the differences between self and other. The individuating quest is one in which we constantly ask ourselves who we are and why we are that way. As it progresses, the identity constructions we have unconsciously acquired are challenged and dissolved to some degree. They are not necessarily removed, but they are rendered more arbitrary, less absolute. In this sense, they are differentiated from the objective Self and sense of self. Factors of identification with various attitudes and totems are gradually transformed into factors of relationship between an I and a You.

While the developmentalist notion of individuation has mostly to do with construction (or development), the concept of individuation I am describing involves mostly deconstruction and unlearning. The initiatory stage of individuation is the dissolution or what I call the animi work. It is this stage that is most turbulent, eventful and resounding with archetypal images and numinous affects. After this, a more constructive phase begins, albeit slowly and uncertainly. This constructive phase I would consider more of a self-organization than a construction. It is not willed or determined. I suppose it could be considered more genuinely developmental or emergent.

This self-organizing process is significantly characterized by languaging. Languaging ushers the developing self into narrative form where the robustness of our identity is connected to the robustness of the narrative we weave or interpret from our observations of and interactions with the Self. Instead of an infantile "inner child", the core of this developing self is the dissolution initiation or the symbolic death and birth. The hero-animi syzygy stands as the parents, although both aspects of the syzygy will also serve to characterize the developing self. What unfolds from the relational engine represented by the syzygy is the narrative of self, which is a narrative about the relationship with the Self and with the objective sense of self in relationship with others and otherness. The narrative structure of self is more robust and efficient as a system than the old, compartmentalized or scripted self (pre-individuation). The old self functioned more like a memory bank or file cabinet containing sets of scripted actions and reactions. To simplify greatly, it is almost as if one's identity is a handful of playing cards. The identity strategy involved play specific cards from this hand in response to various situation. But the cards themselves don't change and neither do the rules of the game. But in a narrative, everything is woven together, adapting and evolving. A piece of identity, like a "character" is changed by its relationship to other pieces. Robustness develops or emerges from interrelationship of parts, especially as that interrelationship serves to facilitate the Self's organizing principle (which is dynamic and adaptive).

Describing this revised sense of identity is difficult due to the complexity of the object being described. I don't want it to sound overly mystical, but it is hard to avoid that. Mystical wrappings aside, one of the most succinct and yet rich representations of the individuated personality I know of can be found in the emblem sequence of the alchemical text,

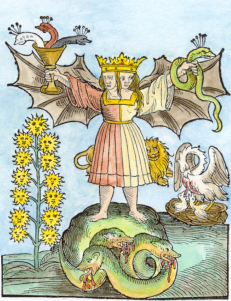

The Rosarium Philosophorum. Emblem 17 depicts the "Demonstration of Perfection" (the image below is from Adam McLean's Alchemy Website):

There is a bit of grandiosity in this image (like many alchemical images) and especially in its title. It would make it seem (at least to many modern day people) that alchemy is about spiritual attainment or enlightenment. At times the differentiations are subtle, but I don't think this is actually so. Emblem 17 is the final sequential emblem in the Rosarium sequence. It corresponds to the creation of the Red Stone. The main figure represents what I am calling the syzygy, a union of hero and animi. The "offspring" of this union are depicted by the sun plant with its 13 sun fruits (pertaining to the alchemical magic numbers of three and one, where the one is the product and the union of the three). In alchemical terms, this could also be expressed as "Projection", or the use of the Philosopher's Stone upon base metals to turn them into Philosophical Gold. In more psychological terms, this is equivalent to what I call valuation. But in this emblem, the valuated product is placed on a lower level than what is depicted opposite it (on the right) . . . that is: the Pelican feeding its young with its own blood. The idea behind this image is that what we nourish and recognize and valuate is nourished self-sacrificially and by feeding it with our own life blood. This sacrifice doesn't mean death to "save" another. It merely means the feeding of the other from the deepest part of the self without being defended or fortified. It suggests that there is something young and in need of nourishment in everyone. To valuate and recognize the others we interact with is to feed them with our own blood, to nourish them and help them grow, to mirror them. That's easier said than done, of course, because we have to first learn what it means to really nourish someone without manipulating them for self-serving reasons.

Behind the syzygy figure is a "subdued" lion. The lion in alchemy is typically a symbol of the acid that can dissolve or "devour" gold or sulfur. It also represents instinctual appetite and drive. It is the engine of dissolution. Its place in emblem 17 suggests that the instinctual drive for dissolution (and therefore transformation) is controlled and directed. It is still behind or subconscious, but recognized and utilized. It is not dangerous in the way it seems to be earlier in the opus. As dissolving acid, the lion can also correspond to Mercurius. It is like the transformative drive of Mercurius. As a drive, it is part of nature (the animal kingdom).

Beneath the syzygy, there is a three-headed serpent devouring itself. The serpent's body also looks like a mound of earth. It is a representation of the element Earth or the Body part of the body, soul, spirit triune self. The serpent here is also an instinct symbol. As Body/Earth, it represents the "basest" or least "intelligent" instincts like aggression and destruction . . . but also regeneration. As Earth, it is prima materia, the foundation of the alchemical opus. It is in a state of continuously devouring and regenerating itself, just as earth-as-soil consumes and gives birth to plants. The value of soil is immense and rarely recognized. I recommend Michael Pollan's book

The Omnivore's Dilemma for some interesting but scientific discussions of the complexity of ecosystems that rely initially on soil. Pollan's discussions really grant soil and grass the mythic richness they deserve. The understanding of Earth and Body in alchemy has much in common with a more scientific treatment of earth-as-soil like Pollan's. The devouring/regenerating serpent also ties back into the death and rebirth initiation experience upon which the entire opus is based.

The wings of the syzygy in emblem 17 are dragon or bat-like wings. The meaning of this come partly as a contrast to the 10th emblem, which also depicts a syzygy figure corresponding to the creation of the White Stone. The syzygy in the 10th emblem has dove or angel wings, suggesting spirituality. The 17th emblem's dragon wings show a more chthonic transcendent quality. What lifts up transcendent thought in the 17th emblem is more instinctual and more directly related to Mercurius. The suggestion of this evolution is that spiritual thought, although potentially transcendent, is still imperfect and incomplete. It is still mired in some degree of delusion . . . and the delusion is precisely a matter of rejecting the instinctual or bodily aspect of spirit. In emblem 10, spirit and body are still essentially conflicted. By emblem 17, spirit and body/instinct are the same thing. The alchemical opus (especially as depicted in the Rosarium sequence) is distinctly anti-spiritual. Alchemy is directed at valuating Body/Earth rather than at exalting spirit, and this differentiates it from most spiritual systems of enlightenment and attainment. It also makes alchemical mysticism much more modern and compatible with scientific mindedness. As one of the chief precursors of modern science, this should not really be that surprising.

Still, the small but ardent interest of modern people in alchemy (much of it inspired by Jung) typically contributes to the misunderstanding of alchemy (through occult or New Age orientations) as a spiritual process or discipline. I see alchemy as more about ethics and valuation of otherness and the devalued (what was devalued by the overly spiritualistic view of medieval Christianity). More than every before (arguably more than it was in the middle ages), the alchemical worldview (interpreted into modern psychological language) is relevant. It is fully compatible both with the modern push to valuate and respect cultures in themselves and also with modern ecology and environmentalism that seeks to treat nature as complex and alive and worthy of respect. In the previous Christian eras, nature and instinct were "animalistic" and "base" or even of the devil. The movement away from that perspective was presaged by the alchemists, albeit is cloaked, symbolic language and fantasy. I wouldn't go so far as to call something hermetic a "movement" of any kind, but the alchemical imagination is still capable of informing (and perhaps even improving) "postmodern" cultural development and thought.

The final element of the 17th Rosarium emblem is the iconic movement of three serpents into one. Adam McLean colored the three serpent on the left the three colors of the opus (black, white, and red) and the single serpent on the right green (suggesting "Nature" or the natural). The three serpents are contained in a cup and could be seen as the phases of the Stone as it transforms within the alchemical vessel. The green serpent is not contained, but it is coiled in a slightly Uroboric fashion, suggesting reciprocating energy or life. We might call this serpent the Nature that is perfected by the Art (in the "Demonstration of Perfection"). Therefore, we can gather from this that the "demonstration" is not a "display" of perfection. Rather, like a scientific experiment, it demonstrates a process of transformation that results in the perfection or valuation of Nature. In other words, the notion of complex intelligence is dissolved away from the ego and distilled until it can be be recognized as an aspect of nature or of complex dynamic systems, the principle that organizes life. It is this Nature that is exalted by the Work, by the Demonstration of Perfection. Nature, not the individual. It is the Other that is valuated and transformed. In Emblem 19, this Other-as-Nature is depicted as Mary being crowned by the Trinity. Just as Mary was exalted or "perfected" by her impregnation by God/spirit, so is Nature/matter/instinct exalted through our complex valuation of it, enabling it to be seen for its true complexity, its deep order and worth. And Just as Mary gave birth to Christ (who like the green serpent in emblem 17 dies and is reborn), so the valuative alchemical process gives birth to the Filius Philosophorum, the self-perpetuating Work of valuation. In other words, what we valuate has the capacity to spread and multiply valuation. It is, in essence, its own agent. It is not an act or creation, but a way of relating that feeds the young in the other with its own blood. And what is nourished is more likely to turn and nourish someone or something else. The root of this valuating agency is not human will, but nature itself (as a kind of self-organizing life force). Human will is merely the self-sacrificing vessel that passes it along or facilitates it.

The Coronation of Mary (and Crowing of Nature/Earth/Body/instinct/matter).

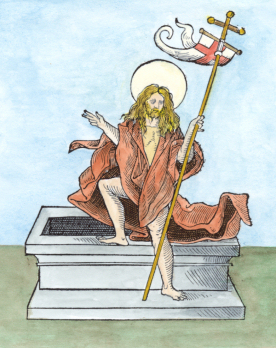

The Resurrection or the birth of the Filius Philosophorum.

The alchemical opus depicts an adult individuation process, and one that extends far beyond Jung's own concept of individuation. In this alchemical form of individuation and initiation, fully adult reflection and meditation is needed. The Self is recognized and elaborated and consciously facilitated in ways that no child is equipped to accomplish. The recognition of the Self in children lacks the necessary languaging sophistication. It is typically fragmented and spread out among various centers of personality (many of which might be external or projected). In this scattering of Self, there is also much confusion between Self and other psychic structures. But this is not at all to say that archetypal images do not arise in or powerfully affect children. Quite the opposite is true. Archetypes are abundant in the minds of children. What is lacking is an adequate philosophy or languaging system. A child can be moved by a representation of a hero, but this doesn't mean that the child knows how to channel the hero or interpret it into realistic expression. Much psychic energy is exhausted in childhood (as well as adulthood) trying to defend the fragile ego and keep it from falling apart. It doesn't occur to children that for the real hero, the ego must be dissolved or dismembered and then reconstructed in a much more selfless and valuative way.

Although I recognize most of my disagreements with the developmental Jungian paradigm as heavily influence by differences in dialect, where individuation is concerned, I see much more overt conflicts. The understanding of the syzygy and its central role in individuation I have does not have an adequate counterpart in the developmental paradigm. In disregarding or even pathologizing the hero and animi (and also at times the big-S Self), developmental analysis shoots itself in the foot. The animi work is the archetypal core of healing and psychic growth. Without the push and guidance of this process, I see little chance in any healing that could benefit from individuation's reconstructive dynamic. With that absence, I would predict prolong analysis with a highly addictive or habit-forming component and complicated, often unproductive projective attachments of patients to analysts.

It is arguably a coincidence, but this is precisely what we often see in psychoanalysis and developmental Jungian analysis. Patient and analyst might meet four or five times a week, and analysis could last many years . . . even decades. In that climate, the likelihood of indoctrination of some form of habituating conditioning is high. This is not to say that such analysis is therefore fraudulent or that some patients don't benefit from such treatment. But the prolonged and intensive character of analysis suggests that there is no kind of initiation going on. In psychoanalysis, this may be less of a problem, as initiation is pretty far form the stated goal. But in Jungian analysis, even developmental Jungian analysis, so many of the trappings of the process are influenced by initiation motifs and other mysticisms. There may even be encouragement of sorts for the patient to imagine his or her analytic forays into the unconscious as kinds of initiatory experiences (certainly the literature often gives this impression). There may be a degree of misrepresentation here.

On the other hand, I would not advocate the prescription of initiation in analysis. Most people that seek analysis are not driven to do so out of "initiation hunger". Nor is initiation a safe bet as treatment for more serious psychological disorders. It may work (if done correctly), but it is not a first resort option. The problem as I see it is that there are a significant number of people seeking analysis or psychotherapy or who are drawn to Jungian ideas who are suffering from initiation hunger and struggling with the gravity of dissolution. Presented with the option of a valid initiation, many of these people would probably abdicated or end up failing, possibly to the detriment of their mental health. But plenty of people who benefit from initiation, and among these people, initiation may be the most effective form of treatment. In other words, many patients in psychotherapies might be receiving the wrong form of treatment . . . even many more than most people suspect.

Although initiation sounds a bit arcane and dangerous to us, we should try to remember that it is one of the oldest institutions of human culture and (if my theory is remotely valid) we even have innate psychologies fit for initiatory transformation (i.e., the hero and animi archetypes appear to be inherent and associated with biological/instinctual roots). Today, we have no effective institutions of initiation. But the absence of these institutions leaves a large void in the modern human psyche. We crave initiation's organizing principle even if we no longer know how to recognize it or implement/institutionalize it. By default (as they are the closest thing to it) psychotherapies become domains of initiatory longing, disease, and expression.

My suggestion is not that analysts should remodel analysis as initiation, but that analysts should develop a much better understanding of initiation and train to become capable of recognizing and understanding initiation hunger and acting as initiators for those patients who suffer from some kind of initiatory disease. Of all the psychotherapeutic paradigms I know, Jungian theory most lends itself to such knowledge and training. Because of this, it also tends to attract a clientèle more often affected by initiation disease. My concern is not the making over of the psychotherapy industry as an institution of initiation. As a Jungian, I am concerned with the ability of Jungian analysts and Jungian analysis to effectively treat Jungian patients and the Jungian tribal identity. I stand against the residual hypocrisy that threatens to neutralize Jungian thought and render it obsolete.

Despite intents interest in psychotherapeutic theories and methods, I have chosen not to pursue Jungian training largely because I do not believe enough in the system of analysis is teaches. On the other hand, I don't believe I have a more viable alternative (except where treatment of initiation disease is concerned). In the literature I've read, developmental Jungians commonly insist that the form of treatment they practice is just the form of treatment their patients need. Some criticize classical Jungians who "ignore the transference" or "have no effective treatment for more serious personality disorders". I am not convinced, but I also cannot evaluate these claims as I have no access to their patients nor can I "test" alternative treatment methods on them. My own experience is that fewer people with Jungian interests or orientations than I would have expected seem really ready to undertake an initiatory form of individuation. I do see plenty of people with initiation hunger, though. But of these, most are not really ready or willing to endure the initiation process.

Yet, as we look around ourselves and our culture and fellow people, initiation themes still pervade our narratives of maturation and our art and fantasy. Many adults (maybe most) seem to look at various experiences in their lives as initiatory. But rarely are these experiences organized or institutionalized in any way. They are coincidental and unpredictable. Many of them may even fall upon us like some kind of "bad luck" that we eventually reorient ourselves by. It is strange that something so important to the human psyche and to human society is so fragile and so commonly overlooked and misunderstood. Even in Jungian thought, where initiation symbolism essentially dictates the whole theoretical structure, initiation as a living cultural and psychological function is left largely in the shadow.

This is an extensive reaction to such a short paragraph of text, but hopefully it will serve as an orienting preamble as I continue to discuss the rest of Knox's quote.