It seems like the self involvement of the individual is at its peak during the individuation process. Jung calls this the individual's 'sacred egoism.'

An excellent point, Joe. I hope you will forgive me for the winding, essayistic, attempt to investigate these issues that follows. Apologies ahead of time for convolutions and pedantry as I try to "think out loud" to get through the woods. You have touched on some issues I am especially fascinated with.

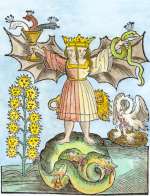

I don't think one can engage with the individuation work without egoisms (both sacred and profane). In the alchemical opus that Jung saw as a precursor of and model for his idea of individuation, there is a battle dramatized between the Old and the New Kings. The Old King can be seen to represent the egoic resistance to surrender to the Self-as-process (and death). The New King, then, would be a symbol of the egoi willing to sacrifice itself to the Self or to the Work . . . the heroic ego.

But during this conflict, the ego as a whole accumulates an increasing gravity of its own, a mass that can withstand the collective's own greater gravity, that gravitational force of affiliations, beliefs, and pressures to conform and "behave". The orientation to the Self seems to provide this gravity or counter-mass. I am guessing that this is what Jung meant by "sacred egoism".

Jung did occasionally reflect on the "hermetic loneliness" of the Work (which is in many ways its greatest burden), but he was a little vague in his descriptions (and prescriptions for resolution). For instance, in the quote you provided, he gets from the "wretchedness" of hermetic isolation to recognition that the love of his fellow-beings as an "invaluable treasure" in one small hop, like it was an A necessitates B equation. That was easy!

I wonder if the Gnostics being purged by the early Church had this invaluable treasure in mind at the moment of their deaths . . . or whether the medieval alchemists who had to keep their works both obscure and secret from "the collective" were grateful for the burdens of heresy thrust upon them. I don't mean to be cynical about Jung's statement. He understood this (the real situation of the heretic), I think. But when Jung talked about individuation, he usually spoke of it as if he were introducing the concept to people who might never have considered it before . . . rather than to "fellow travelers".

Another complication, of course, is that individuation is not really a process of adorning oneself with spirituality and mystical meaning. It's a gathering into consciousness of shadow. The individuant puts on a great deal of shadow mass . . . making one's relationship to the collective all the more problematic and one's ability to love that collective (and one's fellow beings) much more difficult.

Many Jungians seem to have a notion of individuation that is primarily uplifting and empowering. I find this suspect. In my own pursuit of the Work, I have never reached a point at which I could say with absolute certainty that I was better off (happier or more satisfied) thanks to embracing the "sacred egoism" of the individuation process. For every benefit or "empowerment", one takes on twice its weight in burden.

That's why I like Remedios Varo's term "Useless Science" as a synonym for the alchemical Work. The individuant should never forget his or her embrace of egoism or the ultimate cost of that embrace.

I don't think Jung would agree that this creates an obligation to the collective, but more of a recognition of the value of the collective to the individual. The individuation process is not a "sin" against the collective, but instead a necessary step in becoming a productive member of the collective.

Well, you have to take the phrasings of a poet with a grain of salt. Perhaps "sin" is hyperbole . . . but I do feel individuation, taken to a significant enough extent starts to engender a feeling of obligation in the individuant toward the collective. [I thought Jung might have referred to an obligation to the collective in at least one place . . . I'll have to track that down.]

OK, here it is. From

Sharp's Lexicon:

Individuation and a life lived by collective values are nevertheless two divergent destinies. In Jung's view they are related to one another by guilt. Whoever embarks on the personal path becomes to some extent estranged from collective values, but does not thereby lose those aspects of the psyche which are inherently collective. To atone for this "desertion," the individual is obliged to create something of worth for the benefit of society.

Individuation cuts one off from personal conformity and hence from collectivity. That is the guilt which the individuant leaves behind him for the world, that is the guilt he must endeavor to redeem. He must offer a ransom in place of himself, that is, he must bring forth values which are an equivalent substitute for his absence in the collective personal sphere. Without this production of values, final individuation is immoral and-more than that-suicidal. . . .

The individuant has no a priori claim to any kind of esteem. He has to be content with whatever esteem flows to him from outside by virtue of the values he creates. Not only has society a right, it also has a duty to condemn the individuant if he fails to create equivalent values.["Adaptation, Individuation, Collectivity," CW 18, pars. 1095f.]

I think of it like this, human community is highly valued as part of our genetic make-up. We are the "social animal". I would even argue that we have evolved an organ specifically intended to suit the needs of our social/cultural inclinations (the ego). It isn't a "take it or leave it" relationship. We need other people for our lives to become fully "human". We need others to learn from, to influence us and for us to influence. It's a real need, this connectedness, this Eros.

The Eros of "unconscious" communities tends to be tribal. I think Jung was not only un-PC, but wrong when he talked about only "primitive tribes" being subject to unconsciousness and participation mystique. We can see it in our intellectual communities, our political communities . . . it runs rampant in academia. The Jungian community has been called a cult . . . and although this may not be entirely accurate, there are definite pockets of cultishness both in the online and in the professional Jungian communities. All of the Jungian forum communities have their own brands of participation mystique. I'm not sure what flavor Useless Science's will be, because we are so new, but I'm keeping my eyes open.

So, we might hypothesize that this participation mystique, this Eros serves a human "good". It is part of how we have learned to not only survive, but dominate this planet. It is clearly "selected for". It's adaptive. This isn't to say

what it is (that's a very dicey issue), but it

is . . . that much we know.

So, if the process of individuation detaches one from the Eros of the community and its affiliations, connections, and beliefs (and it surely does), we have done something

contra naturum. In the eyes of the tribe, this is a sin. In conventional tribalism, only two roles are afforded for such sinning, the shaman and the scapegoat (and not all tribes have shamans). The shaman is a designated individual who is ritually allowed separation from the tribe (and usually must live outside the tribe), on the condition that he or she will use his or her individuality to act as a go-between moving back and forth between the realm of the "cultural ego" (Jung's collective consciousness) and the unconscious or instinctual Self. As the tribal individuant, s/he is allowed to have the self-consciousness needed to interact with the Self as a singular being (which for other members of the tribe would be hubris, i.e., a sin). In this way, the token shaman can mediate between the tribe's cultural ego and the instinctual unconscious for those occasions when that cultural ego has a "neurosis" or faulty strategy or belief or piece of identity that is going to end up destroying the tribe. In these situations, only conscious individuality can act as the "self-regulator" for the tribe.

This paradigm is even operational in the Jungian community where many people have chosen to see Jung as a kind of shaman who was willing to suffer individuation so they don't have to (this is what taking Jung for a guru amounts to). And Jung deserves some of the blame here, because he wrote a lot about the beginning of the individuation process, but very little about its later stages (although, from some of his writings and letters, we are able to see that he himself confronted at least some of the issues of these later stages . . . for instance, the feeling of obligation to the collective).

The scapegoat, by contrast, is not afforded a very long relationship with the tribe. As soon as s/he is "scapegoated", the jig is up and s/he will face exile or death. But in the ritual of exile or execution, a great deal of tribal Eros is expended.

I bring this up, because in our modern world of huge, global tribes and innumerable sub-tribes, we don't have a ritualized system for including individuals in the tribal Eros. Those who are willing to do enough individuation work tend to find themselves faced with the shaman/scapegoat options. I should have said they find themselves

haunted by these options. These options are fraught with problems in our culture . . . perhaps because they are not tribally endorsed. That is, they have no tribal meaning (for the greater tribe of modern culture). Our culture has become too vast to mediate shamanically . . . and our scapegoats quickly evaporate. Scapegoats have no tribal significance when one can always find a tribe that will guard his or her identity politics. That is, we have so little motivation to cooperate "inter-tribally", because there will always be some other kind of tribe that we can find to embrace us, tolerate our unconsciousness, and grant us the Eros of its participation mystique. So we tend to not learn either from scapegoating or being scapegoated . . . or how to truly cooperate with others or as an other.

We have no real "wilderness for the soul" anymore . . . there is always some acculturated area for us to settle . . . which means the significance of scapegoating (and perhaps even the individual) is practically extinguished. "Severe" individuals don't have a role in our modern "global Eden". They look like fools and cranks to us. Why not join in on the global "love fest" (which is actually the availability of innumerable tribes, tribes for everyone, so members don't have to interact with others in a cooperative way or truly learn tolerance)? In this sense, globalism is like a return to tribalism . . . and we tend to remain unconscious of this. So Jung's warnings about the "collective" and mass-mindedness have not become entirely obsolete.

But the plethora of tribes means there is a bower for every kind of egoism. Egoism seems to be commodifiable . . . and non-ego orientations are too hard to produce quickly, too "expensive" to sell widely. Even the medieval alchemists saw that, to the eyes of most people, their stone was worthless (that recognition upon which Useless Science was named). And I suppose I could go on and on talking about the Blues and the Road . . . but I'll spare you. That's what my book of poems (

What the Road Can Afford) is about.

The main point I wish to make is that, unplugging from the Eros of community is an act

contra naturum, an "inhuman" act, to some degree. One of the main reasons individuation is so difficult is that one must consciously choose to sacrifice this Eros (or the unconscious dependence on it) with the understanding that this will be like ripping out your own guts. But this needs to be done so that one can reform a conscious, Erotic connection to the group. Only with this connection can we have true morality and bear true responsibility for our actions. The tribe does not absolve us of either responsibility (as it does for its unconscious members).

But when we re-approach the tribe with this kind of consciousness, it is immediately perceived as a threat to the participation mystique, the unconscious Eros of the group. So re-connecting is generally denied by most tribes. This is where it gets bitterly lonely, and where our ability to empathize with the tribe and its members is challenged. On one hand, we respect the individual worth and suffering of every member (i.e., we see them as individuals), but on the other hand, that very respect and compulsion to treat them as individuals is taken as an offense or threat by most members of the tribe. After all, the individual is the person who exists in conscious differentiation from his or her affiliations and beliefs/identity politics . . . but as s/he has learned to see all human beings as individuals, s/he has also driven a fissure between a self and that self's affiliations, a distinction not made by the tribal selves in question. So even the "love of one's fellows" will be taken by those fellows as an assault on the core of their being (to the degree that they still maintain aspects of identity through their affiliations and beliefs).

So when you write:

The isolation during the individuation process is not a debt to be paid, but a necessary step towards the individual's ability to contribute to the collective and "learn what an invaluable treasure is the love of his fellow-beings."

I'm inclined to say that the individuant is ultimately at the mercy of the collective or the tribe. Will they

allow him to participate (as an individual), and how will he earn that right in spite of his independence and even heresy? These, in my opinion, become the larger questions.

Once individuation has been completed it allows us to shift our focus outwardly since the overwhelming problem of purpose and acceptance of the ambivalent human nature no longer demands full attention.

The isolation during the individuation process is not a debt to be paid, but a necessary step towards the individual's ability to contribute to the collective and "learn what an invaluable treasure is the love of his fellow-beings."

There are other complications to this scenario, I think. First of all, there is no clear indication of what a "complete individuation" is or entails. Jung (although "officially" claiming that individuation is never complete) seemed to only indicate hesitantly that, at the very end of his life he felt his individuation was complete. Still, many are unwilling to grant him this honor.

The most credible "critique" of Jung's notion of individuation that I've seen has come from the contemporary alchemical perspective of Adam McLean (of the

Alchemy Website). He faults Jung for basing his individuation opus on the emblematic progression from the Rosarium Philosophorum (which Jung used as the alchemical basis of his "Psychology of the Transference"), while not representing this progression in its entirety.

In his

commentary on the Rosarium, McLean writes:

The Rosarium, because of its interweaving of soul and physical alchemy, was of particular interest to the psychologist Carl G. Jung, who perhaps quoted from it in his writings upon Alchemy more than any other single text. Jung, indeed, wrote an essay on the Rosarium series of illustrations under the title 'Psychology of the Transference' which is included in Volume 16 of his collected works, and this provides us with a most valuable foundation upon which to construct an interpretation. Jung, however, only shows us 11 of the 20 illustrations. Furthermore, he suggests that figures he labels 5 and 5a (Rosarium illustrations 5 and 11) are alternative versions of the same figure, whereas on examining the full series of 20 illustrations we find this untenable. Perhaps Jung did not have access to a complete edition of the book, but that as often happens over the centuries, some of these illustrations had been removed from his copy. At any rate, Jung's interpretation is based upon seeing the illustrations as 10 stages, whereas as we have seen there are 20. Indeed, if we read again Jung's analysis of the Rosarium, with a consciousness of the existence of the extended series of 20 illustrations, we will find a further level of integration of the masculine and feminine facets of the soul, which does not contradict Jung's thesis, but amplifies and extends it.

Remo Roth has also written a great deal about the "lost Second Opus" of individuation, and many of these writings can be found on

his website. I have found this "re-discovery" of the second opus deeply important to my own Work and thinking as well . . . although I am not an alchemical scholar and have a few semantic quibbles with some of Remo's prescriptions. Still, this is by any account a major problem for the conventional Jungian notion of individuation. If Jung really did base his idea of individuation on the Rosarium, then he and those Jungian who have followed him have been partially deceiving themselves for many years.

As much as I support Remo Roth and Adam McLean on this issue, I have to admit that, in my experience, the loss of the second opus is largely a moot point. I have met few (if any) people that have seemed to have "completed" this first opus . . . insomuch as I believe it to entail the entirety of the animi work (the recognition and development of the animi relationship toward intimacy, the coniunctio with the animi, the death of the animi-ego (divine hermaphrodite), the differentiation between ego and Self, and the "rebirth" of the ego as partner of the Self (taking over the role original occupied by the animi). Obviously, this process and my interpretation of it are highly debatable . . . and I don't feel certain enough to assign an absolute universality to it. I do feel strongly that it is archetypal, though. And it would seem that this interpretation (psychologization)

can be seen as consistent with the

Rosarium.

My current thinking on the dual opera is that the first is meant to both unite one (as ego) with and differentiate one from the instinctual Self. It is all about the inward movement that establishes conscious individuality while also establishing relationship with the Self (often considered "spiritual" consciousness by many). The second opus is a matter of acting outwardly and devoting oneself to the collective, to others, and to human culture in a way that brings this consciousness (which is itself a kind of "love of the Logos", a connection with Sophia or an Erotic connectedness with and attraction to the gnosis accumulated during the Work) into the tribe without sacrificing it to the tribal tenets. The desire for this re-connection becomes very powerful . . . and so the desire to find a way to be allowed into the tribe as a whole individual becomes a highest priority. This desire pushes the individual toward empathy with the members of the tribe. I think the individual even becomes increasingly inclined to see him or herself through the eyes of others. It is only otherness that matters at this point.

And along with this, the individual has a parallel recognition that "Eros is all". That is, the connection to others is the real reason and drive behind all Work on the ego, all gathering up of gnosis. Gnosis is then committed to ethical action (other-valuation). In the

Rosarium (see emblems 11-17), this "extraverted" movement of Eros is represented by the Sol energy (which is "de-spiritualized", reconnected to the Eros instinct, and generated through the "

multiplicatio" (emblem 17, depicting the solar fruit), which can only be created with a reciprocal and polaric flow of libido between ego and Self and ego-Self and the Other/others).

Emblem 18, the Green Lion devouring the sun, might be seen as a symbolic representation of the sacrifice of the Work (the individuation and one's value as an individual) to the collective instinct or tribal Eros (the Green Lion itself). Although perhaps "extratextual", I would even suggest that the blood dripping from the sun being devoured by the Green Lion is equivalent to the alchemical Red Tincture (the product of the second opus), the transmuted, conscious, Sol energy (which flows, often painfully, through the Wound where the individual was severed from the tribe). Thus, only in the willing sacrifice of the alchemical Gold of the individuation Work (and recognition that this Gold and the Work are, ultimately, a Useless Science, a worthless stone . . . to oneself), can the individual generate this Red Tincture, this conscious Eros Libido for the tribe.

So, although I am still struggling to fully understand these stages, I suspect that this was what Jung intuited and posited as a kind of reconnection with the collective. But I also suspect that these ideas of his were relatively abstract and undeveloped because of his misunderstanding of the

Rosarium-based opus that made it only half what it was originally meant to be.

A very serious additional complication of this mistake of Jung's was that (in my opinion), he wanted to slap on the final (20th) stage of rebirth at the end of the first opus. This had the inevitable result of confusing the hell out of Jungian individuants who manage to make it this far (to the last and

conscious stages of the first opus). It makes it seem that the last "leap" to the New Birth is some kind of grand mystical "becoming" that can only be obtained with an act of faith (unconsciousness). This is clearly not the case when we see all 20 emblems from the

Rosarium laid out properly. The process is not "mystified" in this way, nor does it call on any kind of unconsciousness . . . entirely the opposite.

This misunderstanding leads to an inflation complex in the Jungian individuant . . . who feels compelled to think s/he has reached the final stage when in fact this stage is more than a "full opus" away. The only way (in my opinion) an individuant can overcome this inflation complex (bequeathed to us from Jung himself) is to throw off the Jungian definition of individuation. This false paradigm must be sacrificed in order to progress from the purification of the hermaphroditic body (emblem 8, the final stages of differentiation between ego and Self) to the "resurrection" (return of libido, emblem 9) of the

multiplicatio of the Moon Fruit (emblem 10) that defines the end of the first opus . . . or the creation of the White Stone or White Tincture, the Lunar Consciousness.

But this is all very arcane and complicated stuff . . . and it really belongs in its own thread, a thread dedicated to the inflation (which I have been meaning to start and will soon get to).

Again, my apologies for thinking through this "out loud". I hope it isn't too meandering and digressive.

And of course, this is all a matter of my own opinion, an opinion drawn from experience with these things that may or may not be 1) universal, or 2) interpreted correctly.

But that's what this website is for, in my opinion . . . for working out these kinds of ideas in a dialog or multilog.

Yours,

Matt